There Will Never Be Another Gus McCrae

“The English have Shakespeare, the French have Molière, the Russians have Chekhov, the Argentines have Borges, but the Western is ours.”

All the ranchers liked Lonesome Dove. I was not allowed to watch it as a kid, but at some point I read the first edition hardcover my grandmother gave me. It had belonged to my grandfather. The odyssey of two retired Texas Rangers on a cattle drive from Texas to Montana opens with lines by T.K. Whipple:

“All America lies at the end of the wilderness road…”

Larry McMurtry wrote Lonesome Dove to disabuse Americans of certain prosaic notions about the wilderness road that led them, in 1985, to the Reagan era. An actor in a cowboy hat was president of the United States, and McMurtry had had it with popular portrayals of the frontier and the enduring cowboy mythos. He set out to undermine the romanticization of the West with a hard and ugly hero’s journey. Instead, Lonesome Dove became the ultimate cowboy novel, a great American epic.

In his preface to the 2000 edition, McMurtry pondered his book’s strange fate, a “turnabout I’ll be mulling over for a long, long time.”

“I thought I had written about a harsh time and some pretty harsh people, but to the public at large, I had produced something nearer to an idealization.”

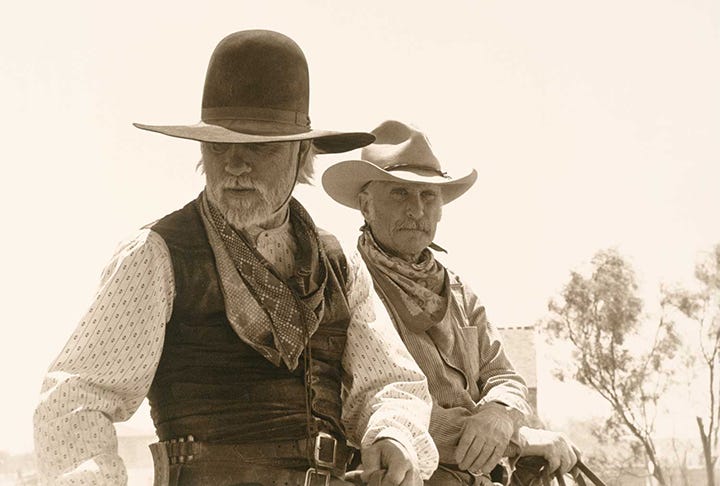

Adding insult to injury, the 1989 miniseries became the most famous Western of its era, with Robert Duvall as Augustus McCrae and Tommy Lee Jones as Captain Woodrow F. Call canonized in the cowboy mind. McMurtry never copped to watching it.

The show is a faithful rendition of the novel, and I think it is beloved for several reasons.

First, it was made before so-called prestige TV made the small screen a respectable venue for artistic endeavors. There is no trace of that self-serious A24 varnish in Lonesome Dove. Much of the four-part CBS miniseries was shot on a dusty Texas set called Alamo Village, built for a John Wayne movie, and filming was said to have been chaotic. The directing isn’t polished and the wardrobe is inconsistent (Janey’s costume comes to mind). All of this to say, the magic is genuine, nothing is contrived.

Duvall and Jones flesh out the book’s leads, retired Texas Rangers that McMurtry conceived of as modern personifications of Dionysius and Apollo, the Stoic and Epicurean.

Their portrayals are iconic, but cowboys love this movie because Duvall and Jones do all their own riding.

“I think that’s what made that picture so great. Everything was real in it.”

Rudy Ugland, wrangler on Lonesome Dove

Duvall’s horse throws him during a Comanche attack scene. He was on a local ranch horse not trained for the movies; set wrangler Rudy Ugland found a “cowboy’s horse” for Duvall, and an unpredictable and testy bronc for Jones’ “Hell Bitch.” In one scene, Jones gallops across a cowtown Main Street to deliver justice to a Cavalry officer in the act of whipping Woodrow’s bastard son Newt, revealing his character’s paternal feelings for the boy and that Jones—who lives on a 3,000-acre ranch in San Saba County, Texas—can ride. Both leads move loose and natural. It makes a difference: Many a Western has been damaged in the viewer’s subconscious by an actor’s rigid torso sitting wooden cutting to a far-off stunt double doing all the riding. That would have broken the movie: much of Lonesome Dove is shot in the saddle.

McMurtry died in 2021. Great a writer as he was, he did not succeed in getting Americans to be realistic.

“I’ve tried as hard as I could to demythologize the West. Can’t do it.”

Now with Robert Duvall’s death this week, another chapter in Western storytelling is closing. If Quentin Tarantino was right and every American era is defined by its Westerns, it remains to be seen what the lasting works of this generation will be, and what they will say about us, and how they will answer our pressing questions.

To McMurtry, the Old West is and always will be the “phantom leg of the American psyche.” The East was New Europe, built by Europeans. The West is American. It built us as we built the West. How a generation feels about its Westerns, which are the stories we tell about ourselves, reflects how it feels about the nation. And how to feel about America has become the pressing question of our time.

“The English have Shakespeare, the French have Molière, the Russians have Chekhov, the Argentines have Borges, but the Western is ours.”

Robert Duvall

If McMurtry was embarrassed by the story that came to define him, Duvall was not. He called Gus his “Hamlet.” Once filming wrapped, he said he had finally done something good, in a career that included To Kill a Mockingbird and The Godfather and Apocalypse Now. There wouldn’t be another Lonesome Dove, Duvall declared, not for 100 years. To him, Gus was a modern-day knight, in his chivalry and love for life and women; an indigenous Texan.

“This character’s like Shakespeare, I think. Let the English play Hamlet and King Lear, that’s wonderful. I’ll play Augustus McCrae.”

Wherever he went, people wanted to talk about Gus. The Argentinian gaucho who wore out his subtitled VHS. The Texas family who wouldn’t let their daughter marry her fiancé until he’d watched all four episodes. He recalled these interactions fondly. Robert Duvall redeemed the Western in his day; he did not begrudge us our myths and heroes, he was kind enough to let us love a cowboy again.

Lonesome Dove, the book, is trending on TikTok. It’s said a new film adaptation is in the works. But whatever Westerns will define our era in American life, we will have to come up with them ourselves. Gus McCrae has passed on, and there will never be another.

. . . nor another Robert Duvall. R. I. P.

"Gus was his Hamlet"... And yet, Duvall was so good in so many roles, before and after. Boss Spearman wasn't Gus, but it was a vintage Duvall western role. Good ride cowboy, rest in peace.