Thrown to the wolves: California ranchers under siege

Wes Woolery reported the first modern wolf kill in California. He and his fellow ranchers have a warning for the American West.

Last year, the state of California ran out of money to reimburse ranchers for livestock killed by wolves.

Wes Woolery, a Shasta County rancher, says the compensation was never enough anyway.

“They can’t reimburse us for children locked inside.”

”We are living in an experiment.”

Jessica Vigil manages Dixie Valley, a large cattle ranch in remote Lassen County. The ranch kids are an hour from school. When they come home, they stay locked indoors.

Vigil says she has done her best to adapt her cattle operation to deal with increased wolf predation. What keeps her up at night is wolf tracks by the sandbox. At least one wolf pack is now frequenting ranch headquarters.

“They have been within 50 feet of the doors of a house where a family with four young children reside.”

Vigil says kids on the ranch are no longer allowed out without supervision.

“As ranchers, we are resilient and have to adapt to the times if we are to survive. However this threat to human life is something that is unacceptable and our hands are tied,” she says. “We are living in an experiment.”

Wolf liaison in Siskiyou County has examined 80 kills

As the wolf liaison for Siskiyou County, Patrick Griffin has inspected 80 wolf kills in the decade wolves have been in Northern California.

“We’re seeing more depredations as a result of wolf kills than bears and mountain lions put together,” he says.

In 2012, new state restrictions on bear hunts resulted in an explosion in black bear populations. Mountain lions have been illegal to hunt in the Golden State since 1990. Locals in the far north say elk and deer populations have been decimated by habitat loss and predator over-population. There isn’t enough natural game left to sustain lions, bears, and now wolves. There are only beef cattle, bred to be trusting and docile.

In Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, wild game is plentiful, and ranchers are allowed to shoot wolves attacking their livestock. In California, where the species is shielded by both federal and state protections, it’s illegal to shoot at wolves to protect livestock or pets. Wolves are getting bolder, and cattle are a preferred food source.

“I’m not a huge advocate for killing wolves, but once they’re in a pattern of killing cattle you have to do something about it,” Griffin says. “All other means first, but if you’re unsuccessful and the killing continues, there must be an opportunity to break that cycle.”

Game cam footage of the Whaleback Pack, known as the deadliest pack in California for its history of severe livestock depredation. Video footage provided by Patrick Webb, wolf liaison for Siskiyou County.

First California wolf kill

In 2015, Woolery reported the first known wolf cattle kill in California. He was moving cows with a bachelor crew of young hands in their early 20s, when one came across wolves on a calf.

He knew to take a photo.

From the spotted owl controversy that gutted logging, to the sucker fish that stripped water from Tule Lake and wiped out farming in the region, to salmon lawsuits that brought down the Klamath Dams, the industrial lifeblood of Northern California has been sucked dry by the Endangered Species Act.

“These are Siskiyou County kids,” Woolery says. “This whole county has been decimated by the ESA. That kid knew what the wolves mean. This is just another nail in our coffin.”

There’s something primal about a wolf kill. It wakes up an ancient knowledge.

“Wolves strike fear in your heart. It’s more than fairytales about the big, bad wolf. It’s engrained.”

Moving his remaining cattle to safety took less than half an hour. By the time Woolery rode back, there were two leg bones left of the calf carcass. He took a second photo.

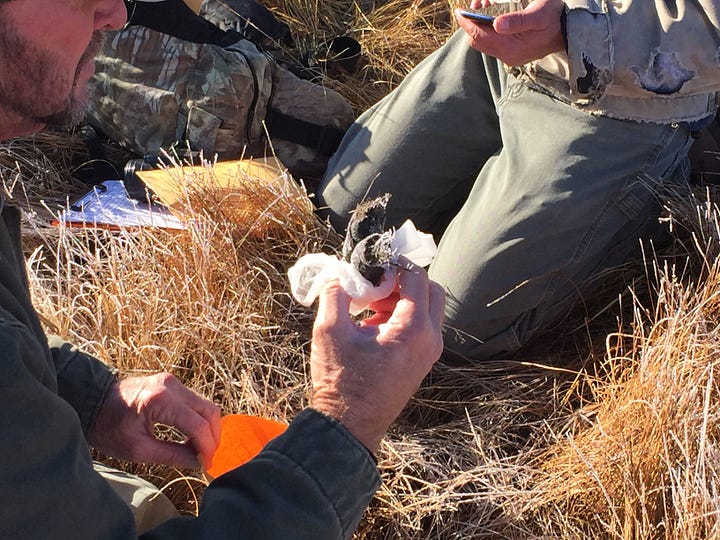

There was no California wolf depredation form in 2015. A biologist from Fish & Game and a trapper brought Woolery the Oregon form, the state name crossed out. Almost every sign of a wolf kill was present at the bloody scene on his ranch that day. The biologist and trapper documented it all.

“I was a lot more idealistic then,” Woolery says. “I believed maybe we still had some sense in the system.”

Despite the emphatic testimony of government trappers and experts that this was a definite wolf attack, officials in Sacramento downgraded the calf to a “possible” or “probable” wolf kill, and the cow to an “unknown.” They told Woolery to keep quiet about the whole thing. They didn’t want word getting out.

He didn’t keep quiet. For years, Woolery has warned every cattle and sheep rancher who will listen about wolves in Northern California. He has watched the wolf population explode, unchecked and—he believes—unnatural.

Where did the wolves come from?

“Some are from encroachment. I think the rest are released.”

Coloradans voted on wolf introduction. Proposition 114 passed with 50.91% support. Of the 49.09% who voted ‘no,’ most came from rural areas, like rugged and ranchy Grand County, where Democrat Governor Jared Polis pulled up in a motorcade in December 2023 to ceremonially release the first gray wolf before returning to his home in urban Boulder.

Wolves came quietly to California. There was no ballot initiative or public debate. Early this year, their numbers hit critical mass.

Many locals believe at least some were planted. They tell stories of strange sightings, out-of-place vehicles, cages found open in the woods. One rancher passed a solid-sided horse trailer on a bad mountain road, driven by two strangers. He could hear horses (or what he thought were horses) inside the trailer. He waved the men to a stop and advised them to let their horses out before attempting to turn the trailer at the road’s narrow dead end. The strangers gave him an odd look and kept on driving. A month later, the rancher spotted a new wolf pack there.

“I couldn’t stop thinking about that truck,” he said later. “Something about it was wrong.”

Woolery says many of the wolves are not afraid of humans.

“They’re not normal. They are too comfortable with humans, they have no natural fear. It’s a matter of time before they kill somebody.”

Theodora Johnson, a Siskiyou County cattle rancher, believes the wolves are not just here because of natural migration.

“It’s all anecdotal, there’s no official story there so it’s hard to back it up. But when you live there and you see it, we’re all fairly certain that’s what’s happening.”

Griffin is confident the wolves found their own way to California from Oregon. There is an unnatural element element at play, he says, but it’s political: The state has over-protected predators. Ranchers are left in the gap, suffering the consequences.

“These wolves take healthy animals,” Griffin says. “Weaned calves, 600 or 700 pounds, they’re one of the most vulnerable age groups because they’re very flighty. When they run, the wolves catch them. A pack of wolves can take down a yearling pretty easily.”

Ranchers ignored

Johnson has run cattle in Siskiyou County all her life. The wolves haven’t found her place yet, though she says it won’t be long. A neighbor was not so lucky.

“I don’t think I’m going to go back to another branding there because it was so heartbreaking,” she says. “The numbers of calves who were crippled and had missing ears and hamstrung and just are totally, totally stressed out.” Her voice breaks.

“It’s so awful because these are the animals that we are here to protect. We’re in charge of them, we care for them, they rely on us for their care, and we’re allowing this to happen. And you can’t do anything about it.”

Unless a wolf is in the act of attacking a human being, lethal take is a felony, punishable by fines and prison time. Ranchers are not even allowed to fire warning shots at wolves attacking their dogs or cattle. The most they can do is put up fladry.

“But if they’ll kill an elk on your front doorstep, I don’t think ribbons tied on the fence are going to do anything,” Johnson says.

Keep wolves wild

Woolery recalls visiting with a rep from Center from Biological Diversity. He wanted to know why ranchers hate wolves so much. “Canadians get along with wolves fine,” the rep insisted.

“I told him: We don’t hate wolves. But what do the Canadians do when a wolf eats their livestock or walks into town? He told me, ‘Well, they shoot it, or shoot at it.’ I said: There you go.”

Human beings are predators with a role in the natural order, Woolery believes. Managing other predators is a human responsibility, for their sake and the sake of their prey. He wants to keep wolves wild. The opposite, he says, is cruel.

“Humans refuse to accept our place in the food chain,” he says. “Having no legal ability to protect your livestock is intolerably frustrating. There’s no where wolves can go in California without being 30 miles from human contact. They get an appetite for cattle, they get comfortable around people, they become the villain. We must be allowed to keep them wild.”

Wolves kill groups of cattle at a time. Woolery has seen wolves consume five pounds of meat from each and move on. Sometimes they devour part an animal while it is still alive, leaving ranchers to mercy kill suffering livestock.

“They are some of our most equal predators. Grizzlies avoid humans. Mountain lions don’t want to kill livestock, they prefer deer. But wolves kill for sport.”

He wonders about a motive even more sinister behind the push for wolves, echoing speculation from ranchers and hunting guides across the West, who believe wiping out cattle ranching, the most decentralized form of meat production left in the United States, serves corporate and government interests, while decimating natural game jeopardizes second amendment rights.

“There’s a push to control food, and wolves are just another blow to public lands grazing and wildlife,” he says. “We only recently established a viable elk herd in Northern California. Depopulate the deer, depopulate the elk we’ve spent millions of dollars to reestablish—game will be a thing of the past. No more need for hunting, no more need for long-range rifles.”

Wolf compensation ran out

Griffin, himself a rancher, sees both sides of the debate. He believes there is room for wolves in the West, but blames the government for poor management, and criticizes urban wolf aficionados for leaving their rural neighbors to shoulder the impact of their idealism.

“Wolves need tolerant people to survive. If there isn’t an adequate compensation program, that tolerance is going to go away,” he says. “At some point, urban people have to share the burden of raising wolves the way the ranchers are now. I think the ranchers have been really good about trying to be cooperative and trying to be fair but at some point when it’s really hitting the pocketbook, it’s going to get ugly. I hate to see that, hate to see ranchers in that spot, taking action into their own hands. There can be substantial retribution for that action which puts the ranchers in more jeopardy.”

As it is, ranchers are put in a position where defending their ability to feed their families could land them in prison. To Woolery, this is the crux of the issue—beyond state-run compensation programs.

“We need to work to get wolves delisted and have the right to defend our rights to protect our private property.”

Reintroduction, or something new?

Woolery has read the Spanish histories of California; detailed records kept over hundreds of years. He’s listened to the elders of local native tribes recount their oral history passed down through millennia. His wife’s pioneer family arrived in the area in the 1870s, his own family has been here for generations. All these histories recount teeming herds of elk and deer. They describe mountain lions, grizzlies, black bears, rivers so full of salmon a man could walk across and not get his feet wet. There’s little mention of wolves, and none of wolf packs.

“When we see wolves, we talk about them,” he says. “I ask biologists: What’s our historic wolf population in California? They don’t have an answer.”

Some people say the wolves in California today are much larger and more aggressive than the few scattered wolves of the past. The Canadian timber wolf is much larger, a serious predator. The packs grow fast, 6-8 pups at a time.

“These wolves are massive,” Johnson says. “They call it ‘reintroduction’ but I think this is new.”

Griffin says it doesn’t matter whether the wolves are native, because they’re here now. Canas lupis are listed as endangered.

“Is it the same wolf? Probably not,” he says. “I don’t think our wolves were as big as these wolves that originated from Canada just a few decades ago. But they’re here now, and we have to deal with them. I would rather focus on what these wolves are doing, the economic and emotional impact they are having, rather than argue about whether they are the wolves that were originally here.”

Those massive herds of elk and deer the American pioneers and Native people and Spanish remember are gone now. Unchecked predator populations, disease outbreaks, and spreading urbanization have wiped out elk and deer, and efforts at reestablishment had barely gained a foothold when the wolves arrived.

“If we’re going to have wolves, we have to manage the wild prey more successfully than we are,” Griffin says. “We have to be more realistic about the carrying capacity for wolves in this state. California tends to manage for revenue rather than benefit of wildlife. That needs to change.”

Romanticism and realism

In the American West, cattle largely graze rough country that can’t be farmed.

“We raise cattle to up-cycle indigestible and inedible plant material into highly digestible, highly nutrient-dense, high quality protein and fat for human consumption,” Woolery says. “Not to feed wolves.”

If there’s one thing men and women in this industry understand, it’s the relationship between calories and sustaining life. He does some back-of-the-napkin math to work out how many steers it will take per day to sustain California’s wolf population:

“The wolves seem to like big calves and young cattle best. A 700-pound yearling only has a carcass of about 450 pounds. Generously, there’s maybe 270 pounds of meat. According to what I’ve read, wolves need 4 to 7 pounds of meat per day. So 50 wolves need roughly a steer per day. That is not accounting for sharing with other scavengers and predators like bear and coyote. So if they only kill for food, which we know they do not, that is closer to 2 or 3 steers per day. On this market, at $2000 per day, times two is $4000 a day, now we are close to $2 million in cattle loss per year for 50 wolves in California, minimum. That is not accounting for stress and production loss added to the surviving animals and ranchers. The decimated deer and elk herd that is hanging by a thread before wolves, will be almost non-existent.”

Pregnancy and wean rates plummet on ranches with wolf impact. Stressed mama cows are less likely to breed up or carry a pregnancy to term. Cattlemen spend untold hours riding range, training large livestock dogs, moving cattle, doing whatever they can to protect their herds—often in vain.

“These people who think we can live with wolves want to impose single-dimensional thinking with a strong dose of romanticism. If they really had to live out here and balance a ranch checkbook, they would think differently,” Woolery says. “These government agencies have got botanists, biologists, every ‘ist’ known to man. But no economist.”

Every beef animal means more than thousands of dollars in immediate value for a rancher. It represents hours of labor, future revenue, years of careful genetic honing, and the attachment and responsibility a rancher feels toward his herd. None of that could be replaced by a check from the government, even before California ran out of funds.

“I don’t have a PhD so my observations mean nothing,” Woolery says. “We’re just dumb farmers, we’re discounted. That’s our frustration—the discounting of our observations, the absolute helplessness we have to live with. We cannot do anything to stop these wolves or any other protected species without losing our freedom and our livelihood.”

Night of the wolves

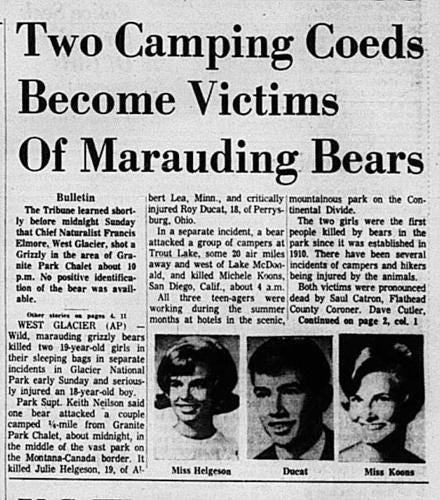

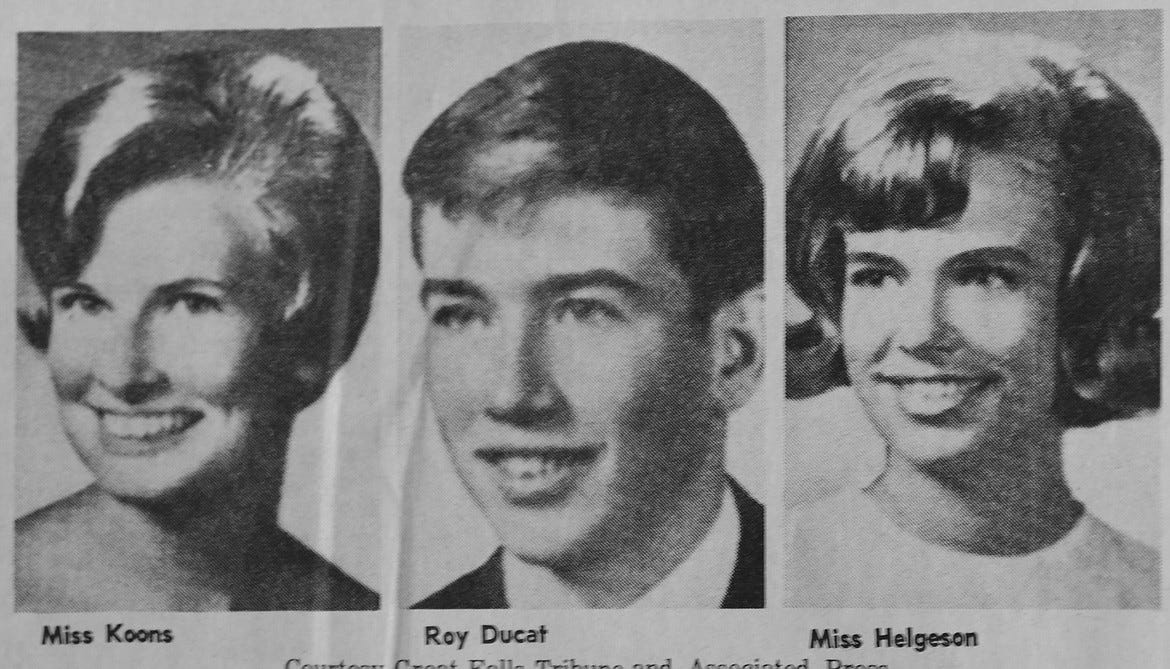

Before the “Night of the Grizzlies” at Glacier National Park in 1967, when two teenage girls were killed in two separate incidents by different bears on the same night, the common belief among Americans was that grizzlies were a non-threat to humans.

A Glacier Park Ranger at the time said: “If you set up a danger index ranging from 0 to 10, where the butterfly is 0 and the rattlesnake is 10, the grizzlies of Glacier Park would have to rate somewhere between 0 and 1.”

To ranchers in Northern California, their rhetoric sounds similar to biologist opinions about wolves today.

“The human memory is short,” Woolery says. “There is a reason they exterminated the wolves in Europe and Ireland, and it wasn’t because they were killing sheep. They were killing humans.”

“The human memory is short.”

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s seminal series on her pioneer childhood begins in her family’s “little house in the big woods” of Wisconsin.

“Wolves lived in the Big Woods,” she wrote.

At night, when Laura lay awake in the trundle bed, she listened and could not hear anything at all but the sound of the trees whispering together. Sometimes, far away in the night, a wolf howled. Then he came nearer, and howled again.

It was a scary sound. Laura knew that wolves would eat little girls.

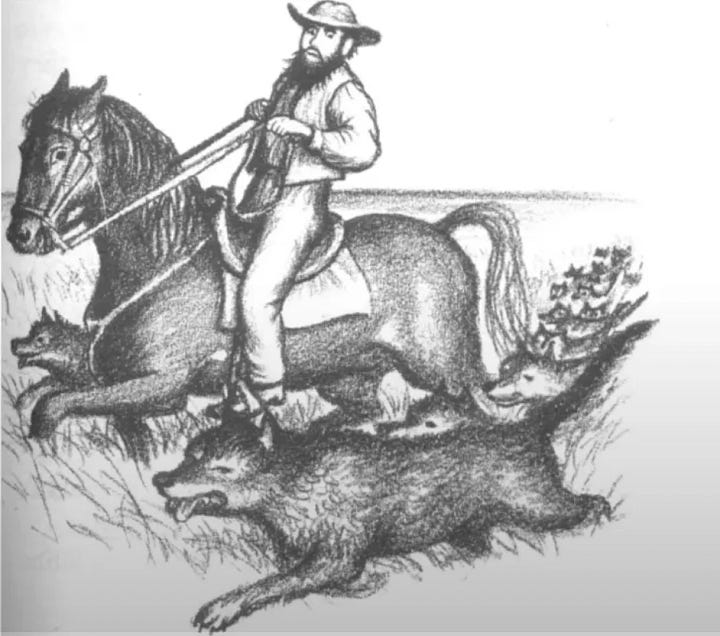

She writes about wolves in each of the series’ eight books, a haunting presence on her family’s Westward journey. In Little House on the Prairie, Wilder’s family has moved to Kansas in a covered wagon. One day, her father is out riding alone on the plains. He is surrounded by 50 buffalo wolves. The wolves ignore him. They trot past.

“They must have just made a kill and eaten all they could,” he says.

His horse tries to run, he holds her back.

“I never wanted anything worse than I wanted to get away from there. But I knew if Patty even started, those wolves would be on us in a minute, pulling us down. So I held Patty to a walk.”

Later that night, the wolves find the Ingalls. They surround the cabin, the sleeping family inside. Wilder can hear their noses sniffing through the cracks in the log walls. They circle the cabin and howl.

Her father watches through the window, his rifle ready. He holds his little girl up to a peephole in the cabin wall. She watches the alpha male, silhouetted on the prairie.

“They are in a ring clear around the house,” Pa whispered.

Laura pattered beside him to the other window. He leaned his gun against that wall and lifted her up again.

There, sure enough, was the other half of the circle of wolves. All their eyes glittered green in the shadow of the house. Laura could hear their breathing.

This is a question I have asked and asked, and it's hard to get an answer from government officials or environmental groups: What is a wild animal? If wolves are nurtured and protected, and can't legally be killed by humans no matter how close their sustained contact with people becomes, are they wild? If wolves are "introduced," moved around in cages and trailers and injected into new areas, is that the behavior of a "wild" animal? So the whole project is based on a bizarre pastoral fetishism in which wolves are scenic, romanticized and sentimentalized, but the people who want to fetishize them won't deal with the reality of the nature they romanticize. The break from reality doesn't end well.

Terrific write-up Keely. The obvious answer is to allow the ranchers to protect their herds (and families). There are some interesting side notes that, maybe 5 years ago, might have sounded a little conspiratorial: where the wolves are coming from, for example. However, maybe now they are not so unbelievable. Chris Brays' writing on Pt Reyes ranchers vs the NPS comes to mind. Colorado's reintroduction of wolves (donated by Oregon, of course) was also done in murky fashion. A bit off-topic, but we had two years of federal denials that our southern border was wide-open, with planes taking off at night. The last administration apparently had few concerns with having entire communities completely unprepared for what happened to them.